Programme

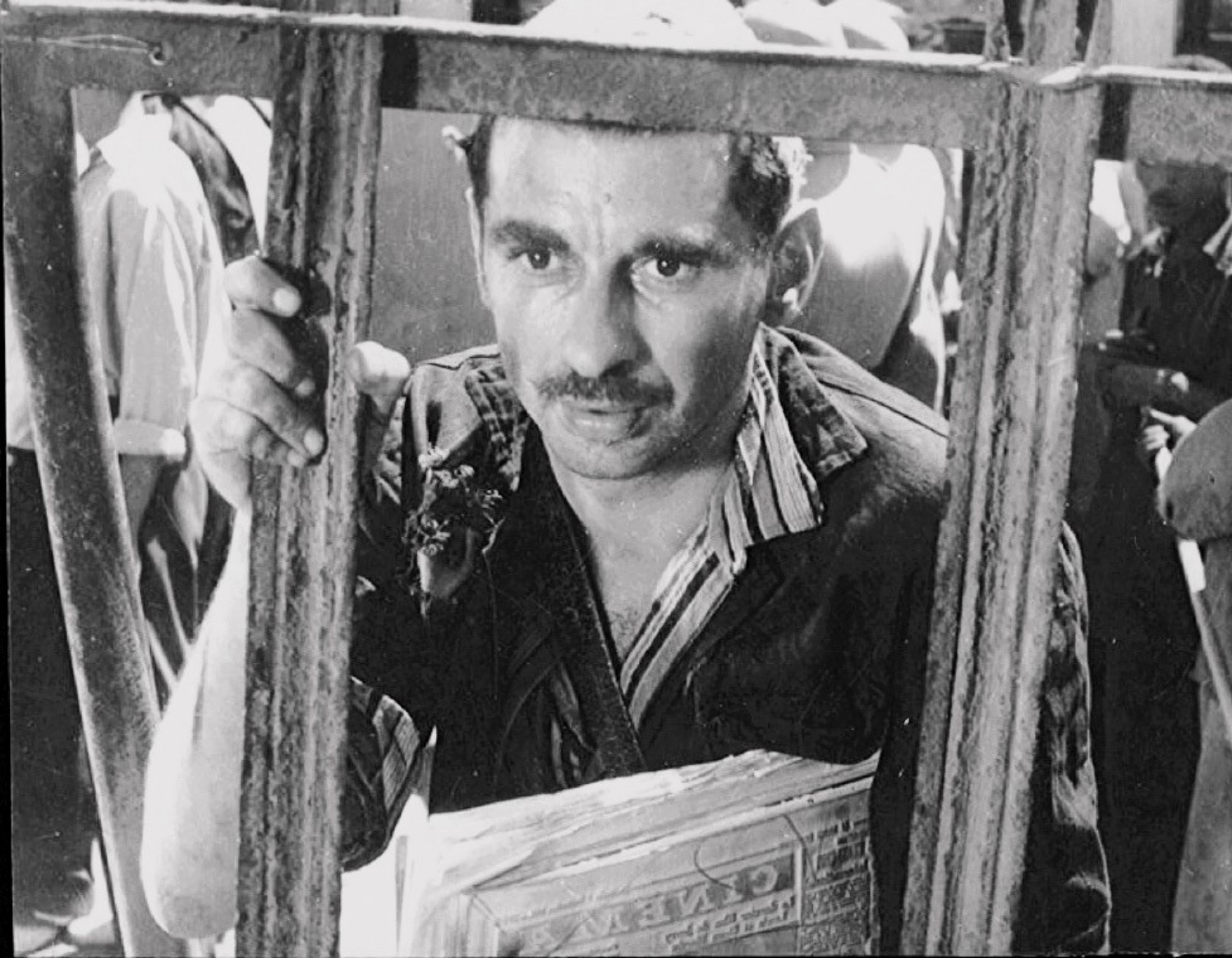

Of Land and Men - The Social Cinema of Youssef Chahine

Born in Alexandria, Youssef Chahine (1926-2008) carried that port city’s exceptional cosmopolitanism in every fibre of his being: a great cinephile, he was always aware of the latest currents in world cinema, finding ways to adapt them for his very Egyptian films. As a teenager, Chahine dreamed he could learn to dance like Gene Kelly, and set his sights on going to the US. He was invited to an internship at the Pasadena Playhouse near Los Angeles.

Returning to Egypt after two years in Pasadena, Chahine decided to try his luck at breaking into Egypt’s then booming film industry. His first film, Baba Amin, proved a hit, and soon Chahine would be well ensconced in the industry, reliably turning out critical and box office successes. In The Blazing Sun, a steamy rural melodrama, he cast a new actor, Michel Dimitri Chalhoub, who took on the screen name Omar Sharif. The film was an enormous hit, launching Sharif onto what would become an international career.

As successful as Chahine was turning out genre pieces, he was aware that a new cinema was emerging. Intrigued by a screenplay he was given set in Cairo’s main train station, the director struggled to find backing for what was seen as a supremely uncommercial venture. Then Hind Rostom, a major Egyptian star, told him she would like to be in the film. Thus, Cairo Station was born – one of Chahine’s unquestionable masterpieces. Even though the film was not a commerical success, Cairo Station provided Chahine a benchmark for what he could do in the cinema. After that, he seemed to adopt a ‘two for them, one for me’ policy, continuing to deliver finely crafted genre pieces while producing some more ambitious, personal work. Over the next 40 years, he would create a filmography within the Arab language cinema that was second to none, with masterpieces such as The Land, The Return of the Prodigal Son, Alexandria… Why? and Destiny, presented and awarded at film festivals around the world. While addressing the complexities of Egyptian social and political life, Chahine’s films retained the appeal and energy of mainstream genre cinema.

A fervent iconoclast, his films earned him enmity from many sides: from government officials who worried that his portraits of Egypt and Egyptians were unflattering, to religious fundamentalists who attacked the sexual sophistication of his films. Chahine’s brilliance at blending convention and innovation may unsettle those with fixed ideas about the Arab world – or about the distinction between ‘commercial’ and ‘art’ cinema – but they will continue to delight anyone with an open mind and a true love of cinema.

English text by Richard Peña, Professor Emeritus of Film and Media Studies at Columbia University.