2024

Test

Seeing the Unseen Godfrey Reggio’s The Qatsi Trilogy

In his Qatsi (= life) Trilogy, former Catholic monk and artist-cum-activist Godfrey Reggio’s critique of technology is [...]

In his Qatsi (= life) Trilogy, former Catholic monk and artist-cum-activist Godfrey Reggio’s critique of technology is not a message, but manifests as cinematic method in the form of non-fiction and wordless, visual narrative. Between poetry and discourse, and via torrents of images transported through Philip Glass’ music, cinema becomes, in Reggio’s own terms, a ‘sacrament’ directly confronting the technicised human world by firing it up.

In his unique universe, images of nature, urbanity, human conditions, space technology, militarism and consumer culture all share the same image space nonhierarchically, articulating what Reggio describes as the ‘unity imperatives’ of technological society. They blend into one another and juxtapose without any plot function. The world is like a new organism – breathlessly pulsating, horizonless, and as real as it is virtual. An image may hiss, scream, stagger, dash off, blink, swerve and swirl – that’s all cinema doing it. Slow motion, reverse backward play, time-lapse, superimposition, computer-graphics, synthetic images, found footage, augmented vision and more are all at Reggio’s free disposal, without symbolic burden, and stripped of conventional usage.

To Reggio, the celluloid film is about the negative becoming the positive; and negation is a way to resist destiny, to bring about change by learning to feel strange for what has become routine. Cinema and imagemaking would remain that liminal space to uphold perceptual estrangement, and camera presence, from within or outside our planet, to make concrete and visible the unseen.

The Other Side of Comedy – The Films of Aki Kaurismäki

Aki Kaurismäki thinks his own films are dreadful. And his deadpan comedies are grim. But the bleaker [...]

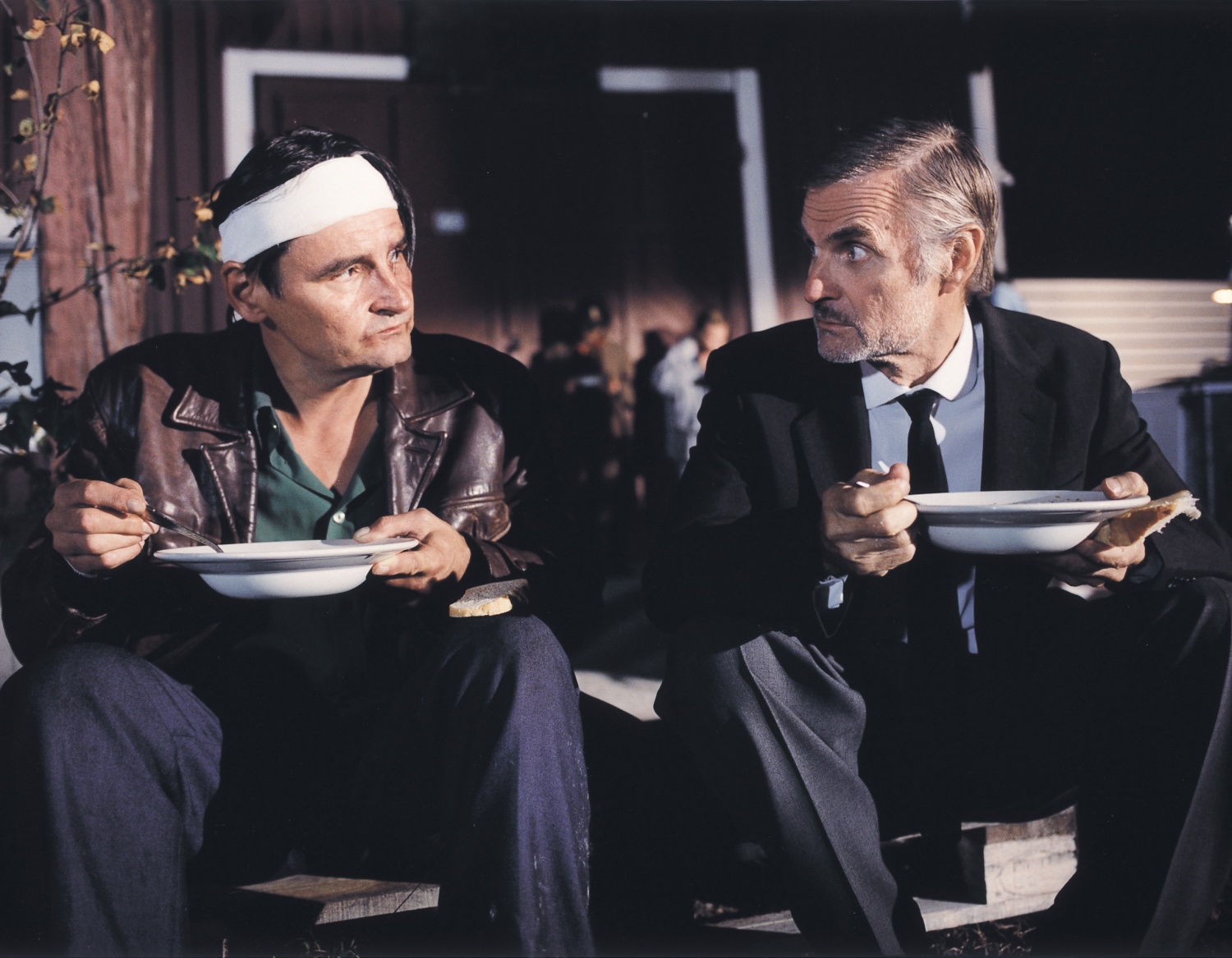

Aki Kaurismäki thinks his own films are dreadful. And his deadpan comedies are grim. But the bleaker the director has become, the more tender his films. No matter how despairing the reality is, his underdog characters always find solace in a sleazy bar, in eccentric rock 'n' roll, and in the company of a devoted canine friend.

Combining the restraint of Robert Bresson with the surrealism of Luis Buñuel, the profound Finn cinephile creates his own cinematic universe of visual stylisation and mordant jokiness for his humane comedy. Highly distinctive but hard to define, Aki’s compositions are simple yet subtly expressive; his approach skews towards a tradition of neorealism, yet flecked with fairytalelike fantasy; his ambiance is nostalgic, yet evoking a modernist vibe. With witty irreverence and stylish intelligence, the artist works dichotomy into an arresting sensibility, championing humanity and spontaneous solidarity while sliding out an unspoken critique towards modern alienation and social injustice.

Imbued with the melancholy lyricism of Edward Hopper, Aki furnishes the humble homes and working spaces with Scandinavian minimalism and a colour palette at once muted and vibrant, where the loneliness of the working class collides with bittersweet tenderness. Retro radios, vintage Cadillacs, and local bands all conspire to tell stories about beautiful losers and bring out a full range of their shrouded but piercing emotions, transforming into his idiosyncratic motifs that emulate the red kettle of his revered Ozu Yasujiro.

vulnerabilities with a weird charm of dry and deadpan humour. Surviving on the margins, his reclusive working-class heroes persevere, trying to walk tall in a world of prejudice, and rebuild their lives against everyday adversity. Hidden behind their poker faces and understated dialogues are existential frustration, alongside suppressed emotions and desires. Whatever fate throws at them, Aki always finds in his heart to reward them with a glimpse of hope – and love – at the end. Comedy rarely comes so bleak, depression is rarely so funny, and miracles are rarely so real.

‘When all hope is gone, there is no reason for pessimism.’ If you can’t cry, why not laugh?

LowellTestEN

TESTTEST

Márta Mészáros: Embracing the Independent Spirit

‘A woman wanting to make films was a joke.’ Márta Mészáros can now blithely laugh at the sarcasm and censorship she faced during her trailblazing, sixdecade career. Being the first woman to direct a feature in Hungary, and the first female filmmaker to win the Golden Bear at Berlinale, she broke barriers in cinema hierarchies and secured herself in the pantheon of auteurs, with an achievement as remarkable as her ex-husband – the legendary filmmaker Miklós Jancsó – yet standing tall in her own distinctive voice in the history of cinema.

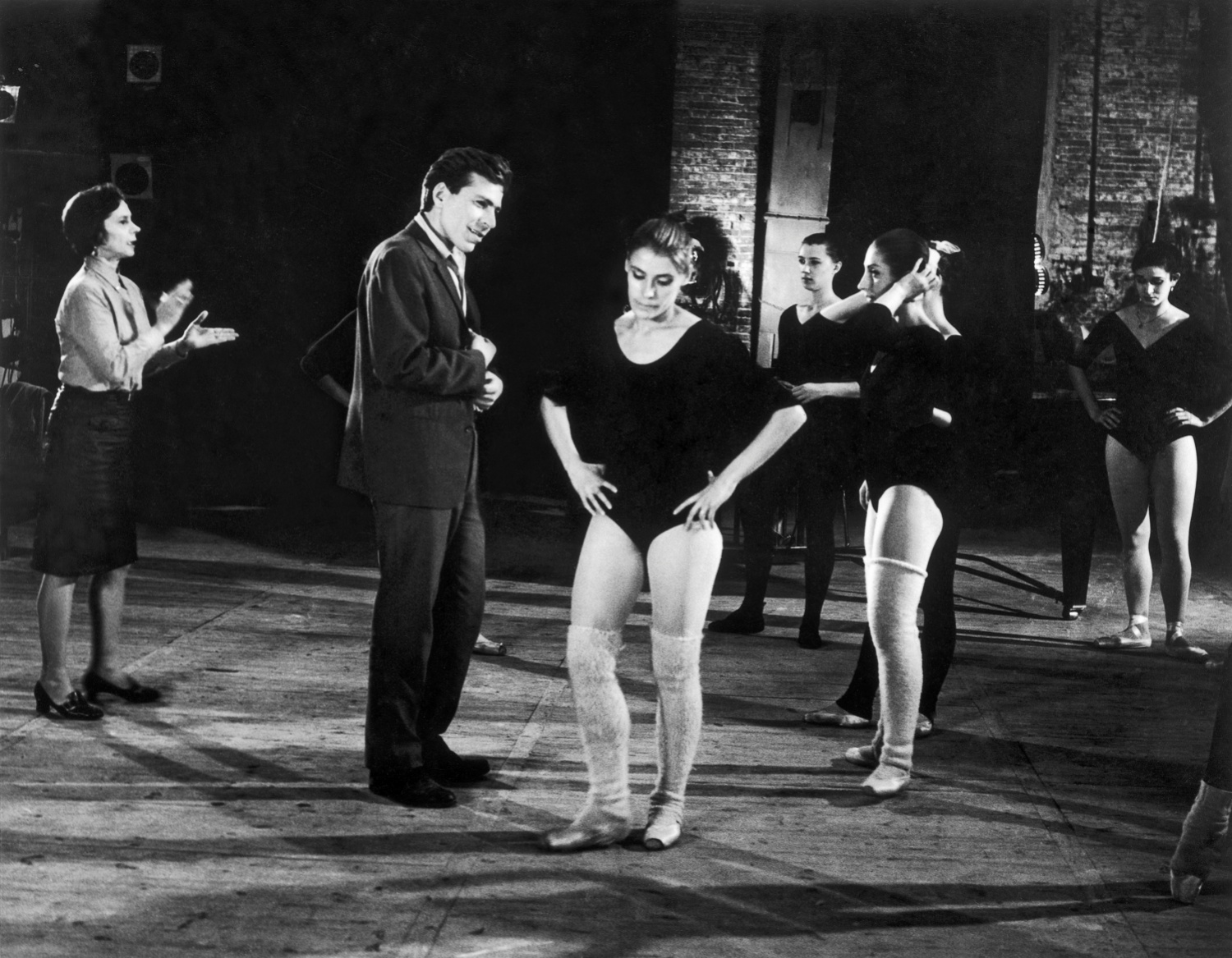

Spending a decade making documentaries, Mészáros honed her dynamic visual style, investing delicate nuances and subtle realism into her exploration of women’s lives – in her own words, ‘to tell their stories honestly.’ Skillfully turning ordinary workplace and domestic chores into private, churning dramas, she places her characters under conflicts and dilemmas where they must make a decision on their own. From bearing a child out-of-wedlock to hiring a surrogate mother, and even giving birth on camera, the Hungarian director is fearless in obfuscating the boundaries between fiction and reality, addressing head-on sensitive and controversial subjects that few dare to challenge.

Márta Mészáros: Embracing the Independent Spirit

‘A woman wanting to make films was a joke.’ Márta Mészáros can now blithely laugh at the sarcasm and censorship she faced during her trailblazing, sixdecade career. Being the first woman to direct a feature in Hungary, and the first female filmmaker to win the Golden Bear at Berlinale, she broke barriers in cinema hierarchies and secured herself in the pantheon of auteurs, with an achievement as remarkable as her ex-husband – the legendary filmmaker Miklós Jancsó – yet standing tall in her own distinctive voice in the history of cinema.

Spending a decade making documentaries, Mészáros honed her dynamic visual style, investing delicate nuances and subtle realism into her exploration of women’s lives – in her own words, ‘to tell their stories honestly.’ Skillfully turning ordinary workplace and domestic chores into private, churning dramas, she places her characters under conflicts and dilemmas where they must make a decision on their own. From bearing a child out-of-wedlock to hiring a surrogate mother, and even giving birth on camera, the Hungarian director is fearless in obfuscating the boundaries between fiction and reality, addressing head-on sensitive and controversial subjects that few dare to challenge.

Mészáros looks at her characters through a minimalist yet discerning lens, almost like an innocent child – the visceral emotions across their faces are captured with exquisite close-ups and freeze frames, and their intense struggles are gently laid bare without value judgment but with a sympathetic caress. Yet she never forgets to quietly admire women’s stamina and fiercely independent spirit, while piercing through the patriarchal manipulation and moral conservatism that her heroines are striving to resist. Despite being lauded as a pioneering feminist, Mészáros never recognises herself as such: ‘I wasn’t making films about feminism. I was making films about people.’

Astonishingly prolific, Mészáros’ themes range from personal independence, female solidarity to reflection on history. In the electrifying characters played by Marina Vlady, Isabelle Huppert, Lili Monori and Zsuzsa Czinkóczi, some parts of her alter-ego can always be seen, referencing her childhood as an orphan, her formative years as an adopted daughter and her rise to become an acclaimed filmmaker. Her own life embodies women’s gender and artistic emancipation, while intricately entwined with Eastern Europe’s sociocultural transformation. In its masterful blends of the personal and the political interwoven with dreamlike memories, real and fictionalised newsreels, Mészáros’ autobiographical ‘Diary Trilogy’, her most acclaimed work, displays a refined, sophisticated film language that merges her own suffering with her country’s tragic history as it unfolded within her own lifetime, evoking agony and catharsis in equal measure.

Now at 92, it’s Mészáros who has the last laugh.

The Girl (a.k.a. The Day Has Gone)

Read more

Binding Sentiments

Read more

Adoption

Read more

Nine Months

Read more

The Two of Them

Read more

Just Like Home

Read more

The Heiresses

Read more

Diary for My Children

Read more

Diary for My Loves

Read more

Diary for My Father and Mother

Read more

The Red and the White

Read more

Red Psalm

Read more

Back to the Screen

Two of a Kind — Auto-Remakes by Master Filmmakers

Remakes have a history nearly as long as Western film culture itself. While some may consider it as proof of filmmakers running out of creative ideas, the master filmmakers do have distinct, strong reasons to revisit their story a second time, and all share one ultimate goal – elevating their own work to absolute perfection.

From silent to talkies, from sheer black and white to vibrant colour, from academy ratio to CinemaScope are among the justified reasons for reprising a film. The reincarnation not only represents technological advances in filmmaking, but also reflects the evolution of time – Ozu Yasujiro’s Tokyo, where his rowdy children lived in his films, shifted from pre-war depression to post-war economic recovery; as Europe was sliding to warfare again, Abel Gance reiterated his indictment, taking the anti-war theme to new horizons through two highly stylised films. Julien Duvivier transposed his dance programme from French sensibility to American sensuality, mirroring the cultural difference and his own transformation after fleeing to Hollywood.

As censorship was relaxed alongside the progression of societies, films that were previously banned or forced to be excised can now return to the director’s ideal version. Inagaki Hiroshi restored in The Rickshaw Man the heart-wrenching scene of his retrained confession of love; William Wyler created an unflinching adaption that stays true to its original theatrical version in The Children’s Hour, without compromise on the homosexual innuendo onscreen. Yet, allusions and subtexts conceived to evade censorship still evoke an enchanting aura and pleasure that is unparalleled.

While almost all directors recreate their work in pursuit of excellence, some regard their second attempt as a new venture rather than pure self-enhancement. Alfred Hitchcock once told François Truffaut that the original 1934 version of The Man Who Knew Too Much was the work of an amateur, whereas the 1956 remake was the work of a professional. If taking it as a MacGuffin, what the Master of Suspense truly meant is likely to be: one is an unpolished gem, one is a processed jewel, and both are arguably equally good. Sharing Hitchcock’s magic touch is Raoul Walsh, who transfigured the crime noir High Sierra into the Western genre with Colorado Territory, a cinematic echo that sees the cool Humphrey Bogart rivalling the composed Joel McCrea.

Leo McCarey made Love Affair when he was 41 and remade it at the age of 59. Nearly twenty years’ life experience and a nearfatal car accident explain his proliferating sensitivity towards life, love and fate, cumulating to the profoundly sublime An Affair to Remember. Unvarnished or refined, raw or mellow, both original and new versions have their distinctive appeal to different viewers. Putting them together can become fascinating territory for analysis, and you’ll come to discover something anew.

I Was Born, But...

Read more

Good Morning

Read moreThe Life of Matsu the Untamed

Read more

The Rickshaw Man

Read more

I Accuse (1919)

Read more

I Accuse (1938)

Read moreChristine (a.k.a. Dance Programme)

Read more

Lydia

Read more

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934)

Read more

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956)

Read more

High Sierra

Read more

Colorado Territory

Read more

These Three

Read more

The Children's Hour

Read more

Love Affair

Read more

An Affair to Remember

Read more