2026

Unscrpited Life: The Cinema of John Cassavetes

When it comes to filmmakers who truly changed cinema, John Cassavetes (1929-1989) undoubtedly ranks among them. Unlike [...]

When it comes to filmmakers who truly changed cinema, John Cassavetes (1929-1989) undoubtedly ranks among them. Unlike those larger-than-life masters, his greatness lies in his ‘smallness’ – with a low budget, he pioneered independent cinema in America; and with an unadorned lens, he captures the profound ‘small emotions’ of ordinary people.

The son of Greek immigrants, Cassavetes empathised with those marginalised by society, searching for identity, love and definition. Starting out as an actor, he believed acting is merely a heightened form of social activity we pursue in our various transactions with the world. In 1959, he collaborated with pals to create his groundbreaking first feature – Shadows, which was declared a masterpiece of the ‘New American Cinema’ by Jonas Mekas.

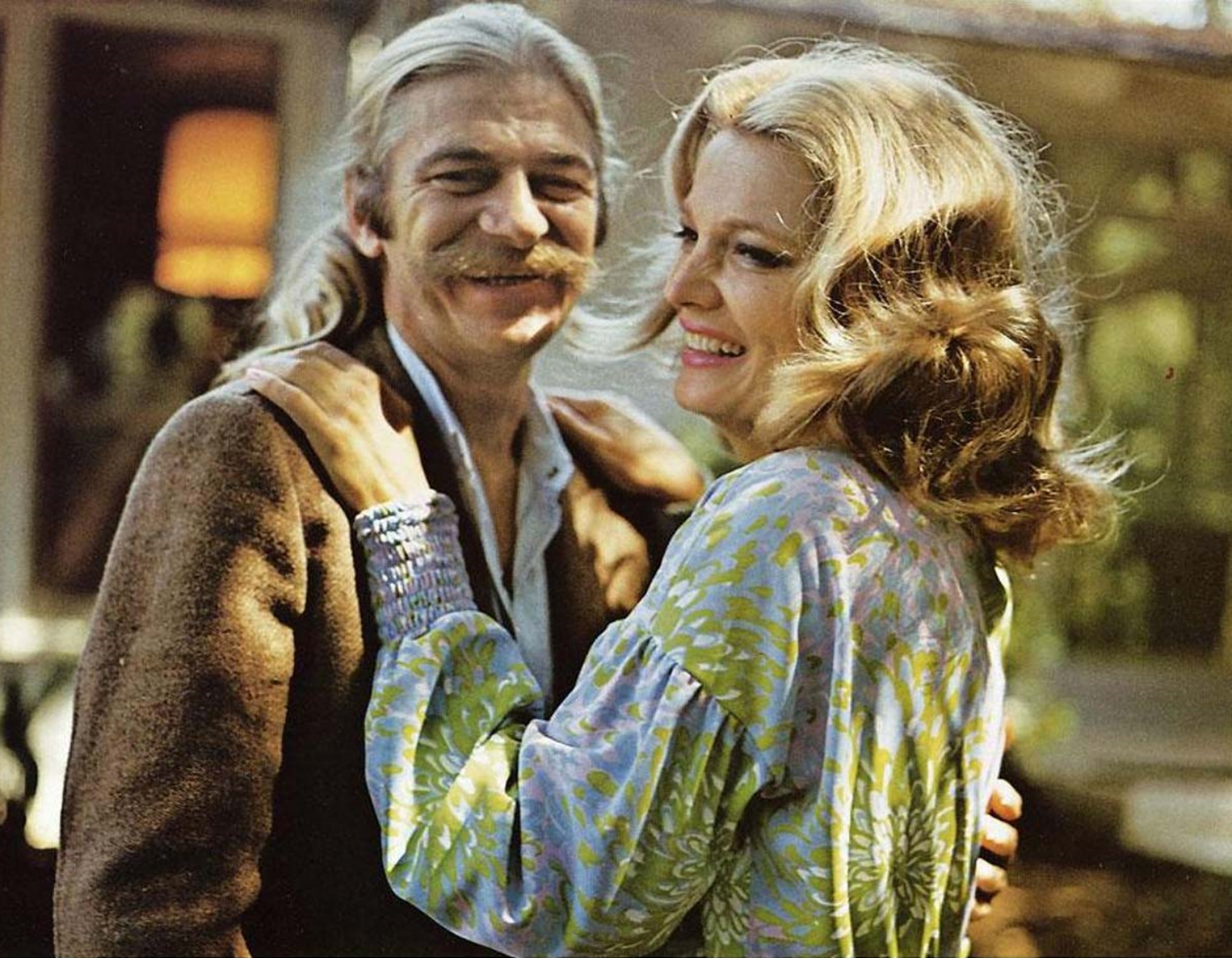

Being great admirers of each other’s work, Cassavetes shared with Orson Welles the view that the actor rather than the director should be the key figure in filmmaking. Eschewing any overt stylisation, he embraced an approach that prioritises his actors and their performances, in a highly collaborative process with his wife-cum-actress Gena Rowlands and his regulars that gives them the freedom to interpret their characters. From Faces to A Woman Under the Influence and Love Streams, they work as a team to explore the ambiguities of human nature, the paradoxes of drama, and the infinite possibilities of cinema. Whether it was Rowlands’ hysteria, Peter Falk’s drunken rambling, or Seymour Cassel’s outburst of rage, their immersive performances splashed forth a raw authenticity of life – natural, vibrant, and brimming with vitality.

While heralding improvisation, his films were usually based on a storyline, and the cast worked from a script. Handheld cameras, unorthodox narratives, occasionally ungrounded compositions, and unadorned set design – what Cassavetes focused on are not visual pomp but ordinary individuals, often with flawed personalities. Yet he rejected any simplistic psychoanalysis; instead his extreme close-ups captured the chaotic and contradictory expressions of their difficult characters. He pushed for emotional honesty, even if it was painful – in some way mirroring his lifelong struggle with alcoholism.

Refusing to be constrained by Hollywood studio systems and traditional dramatic conventions, Cassavetes insisted on his creative autonomy until his death at the age of 59 from cirrhosis. Throughout his career directing a total of 12 films, he struggled with financing his projects, using income from his acting jobs in over 70 films, and even mortgaging his own home. Limited budgets did not hinder his artistic achievements; his uncompromising and unrestrained filmmaking embodies the quintessential American independent spirit that influenced generations of directors like Martin Scorsese and Jim Jarmusch: ‘As an artist, I feel we must try many things – but above all we must dare to fail.’

Shadows

Read more

Too Late Blues

Read more

A Child is Waiting

Read more

Faces

Read more

Husbands

Read more

Minnie and Moskowitz

Read more

A Woman Under the Influence

Read more

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie

Read more

Opening Night

Read more

Gloria

Read more

Love Streams

Read more

Big Trouble

Read more

Rosemary's Baby

Read more

Mikey and Nicky

Read more

Of Land and Men - The Social Cinema of Youssef Chahine

Born in Alexandria, Youssef Chahine (1926-2008) carried that port city’s exceptional cosmopolitanism in every fibre of his [...]

Born in Alexandria, Youssef Chahine (1926-2008) carried that port city’s exceptional cosmopolitanism in every fibre of his being: a great cinephile, he was always aware of the latest currents in world cinema, finding ways to adapt them for his very Egyptian films. As a teenager, Chahine dreamed he could learn to dance like Gene Kelly, and set his sights on going to the US. He was invited to an internship at the Pasadena Playhouse near Los Angeles.

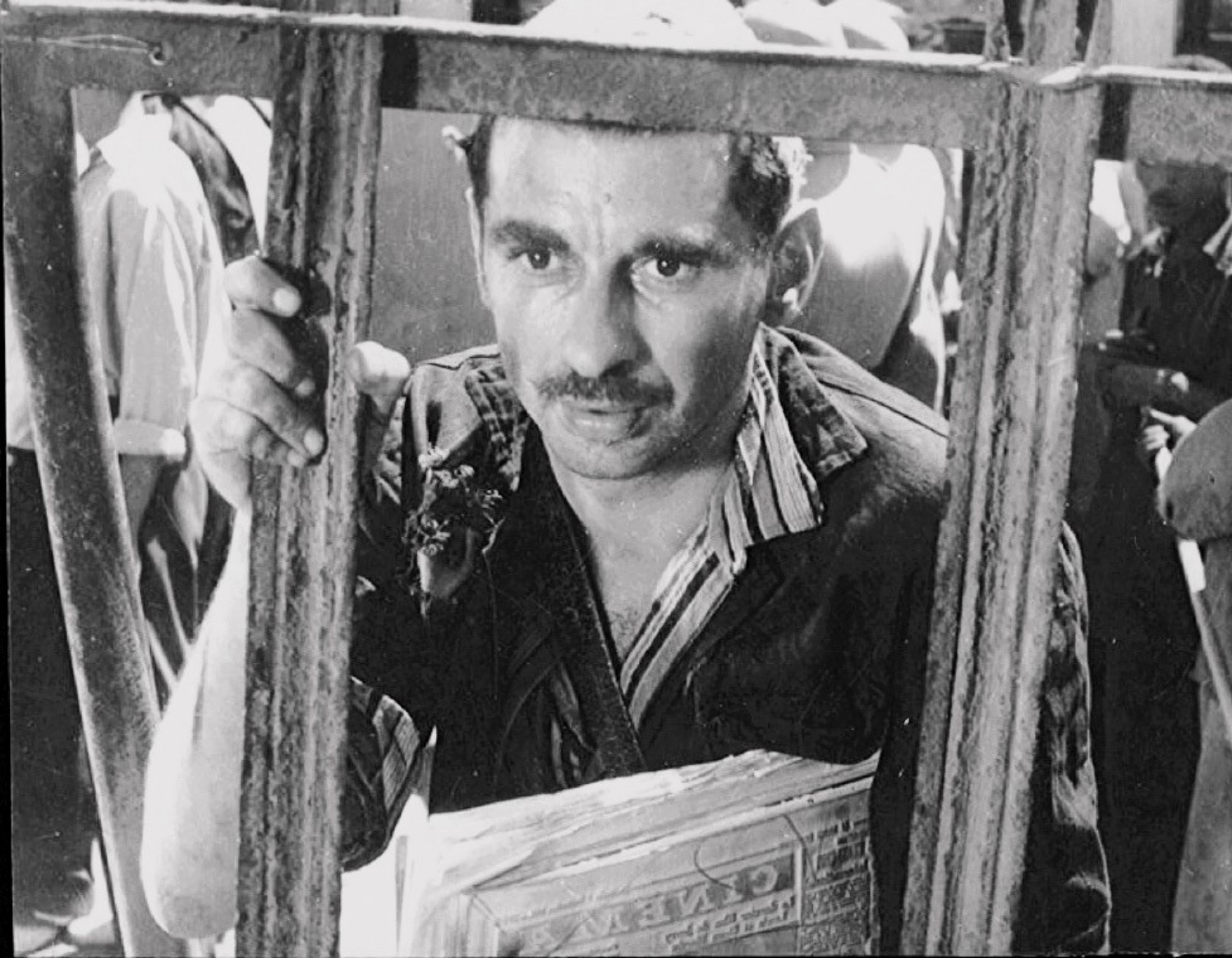

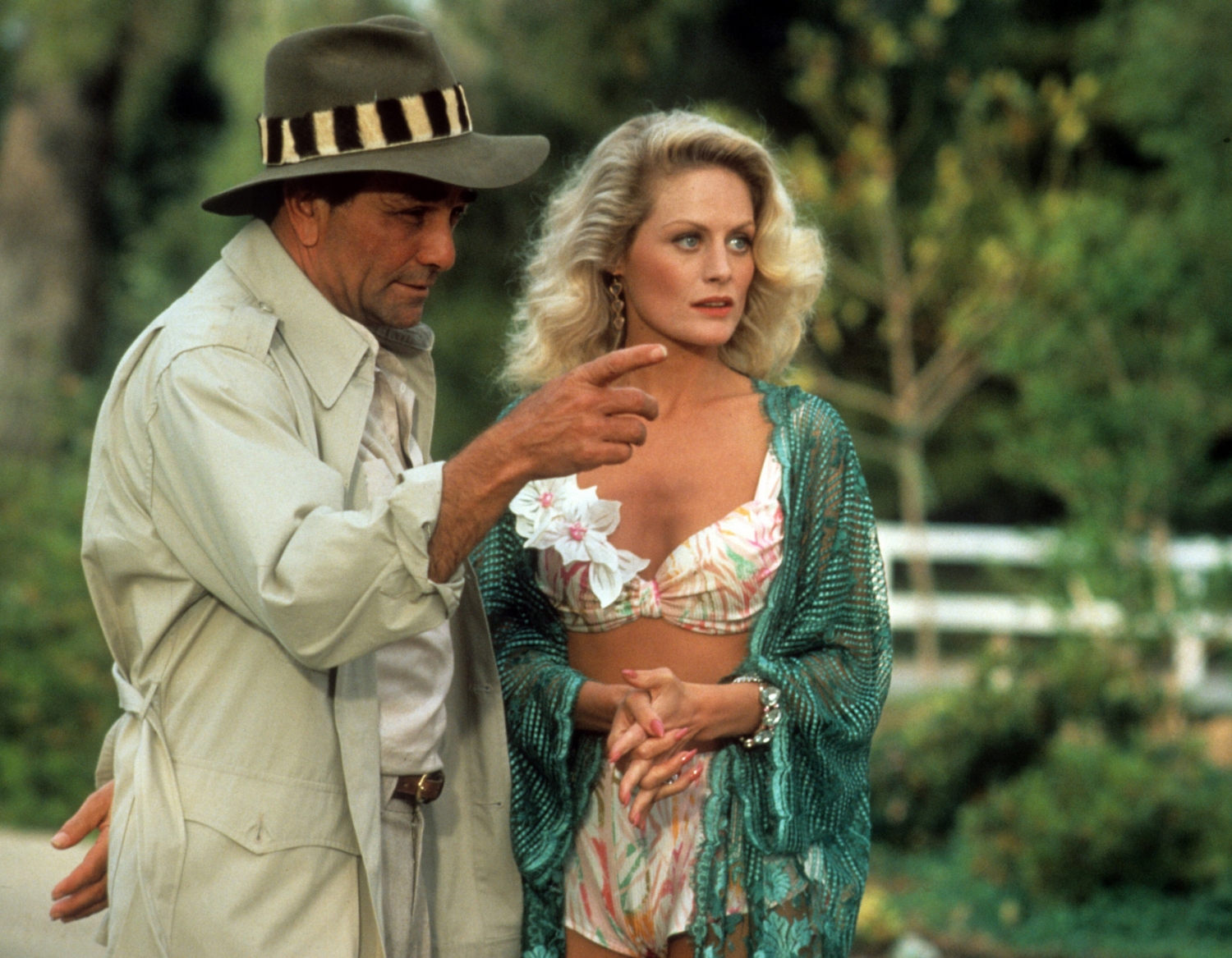

Returning to Egypt after two years in Pasadena, Chahine decided to try his luck at breaking into Egypt’s then booming film industry. His first film, Baba Amin, proved a hit, and soon Chahine would be well ensconced in the industry, reliably turning out critical and box office successes. In The Blazing Sun, a steamy rural melodrama, he cast a new actor, Michel Dimitri Chalhoub, who took on the screen name Omar Sharif. The film was an enormous hit, launching Sharif onto what would become an international career.

As successful as Chahine was turning out genre pieces, he was aware that a new cinema was emerging. Intrigued by a screenplay he was given set in Cairo’s main train station, the director struggled to find backing for what was seen as a supremely uncommercial venture. Then Hind Rostom, a major Egyptian star, told him she would like to be in the film. Thus, Cairo Station was born – one of Chahine’s unquestionable masterpieces. Even though the film was not a commerical success, Cairo Station provided Chahine a benchmark for what he could do in the cinema. After that, he seemed to adopt a ‘two for them, one for me’ policy, continuing to deliver finely crafted genre pieces while producing some more ambitious, personal work. Over the next 40 years, he would create a filmography within the Arab language cinema that was second to none, with masterpieces such as The Land, The Return of the Prodigal Son, Alexandria… Why? and Destiny, presented and awarded at film festivals around the world. While addressing the complexities of Egyptian social and political life, Chahine’s films retained the appeal and energy of mainstream genre cinema.

A fervent iconoclast, his films earned him enmity from many sides: from government officials who worried that his portraits of Egypt and Egyptians were unflattering, to religious fundamentalists who attacked the sexual sophistication of his films. Chahine’s brilliance at blending convention and innovation may unsettle those with fixed ideas about the Arab world – or about the distinction between ‘commercial’ and ‘art’ cinema – but they will continue to delight anyone with an open mind and a true love of cinema.

English text by Richard Peña, Professor Emeritus of Film and Media Studies at Columbia University.

Of Identity and Imagination - The Shifting Landscapes of Arab Cinema

Agonising turns of history, great riches of cultures and heritage. The world of Arab cinema presents an [...]

Agonising turns of history, great riches of cultures and heritage. The world of Arab cinema presents an extraordinary treasure chest to those who dive in and explore its essentials.

Of the Arab nations spanning North Africa and reaching into the Middle East, Egypt has historically been the largest film producer. The country was the first to establish a national cinema, and by the late 1940s was pumping out comedies, musicals and melodramas that played across the region. But when other states won independence through the ’50s and ’60s, and with overseas support kicking in, film industries emerged in countries like Tunisia and Algeria too.

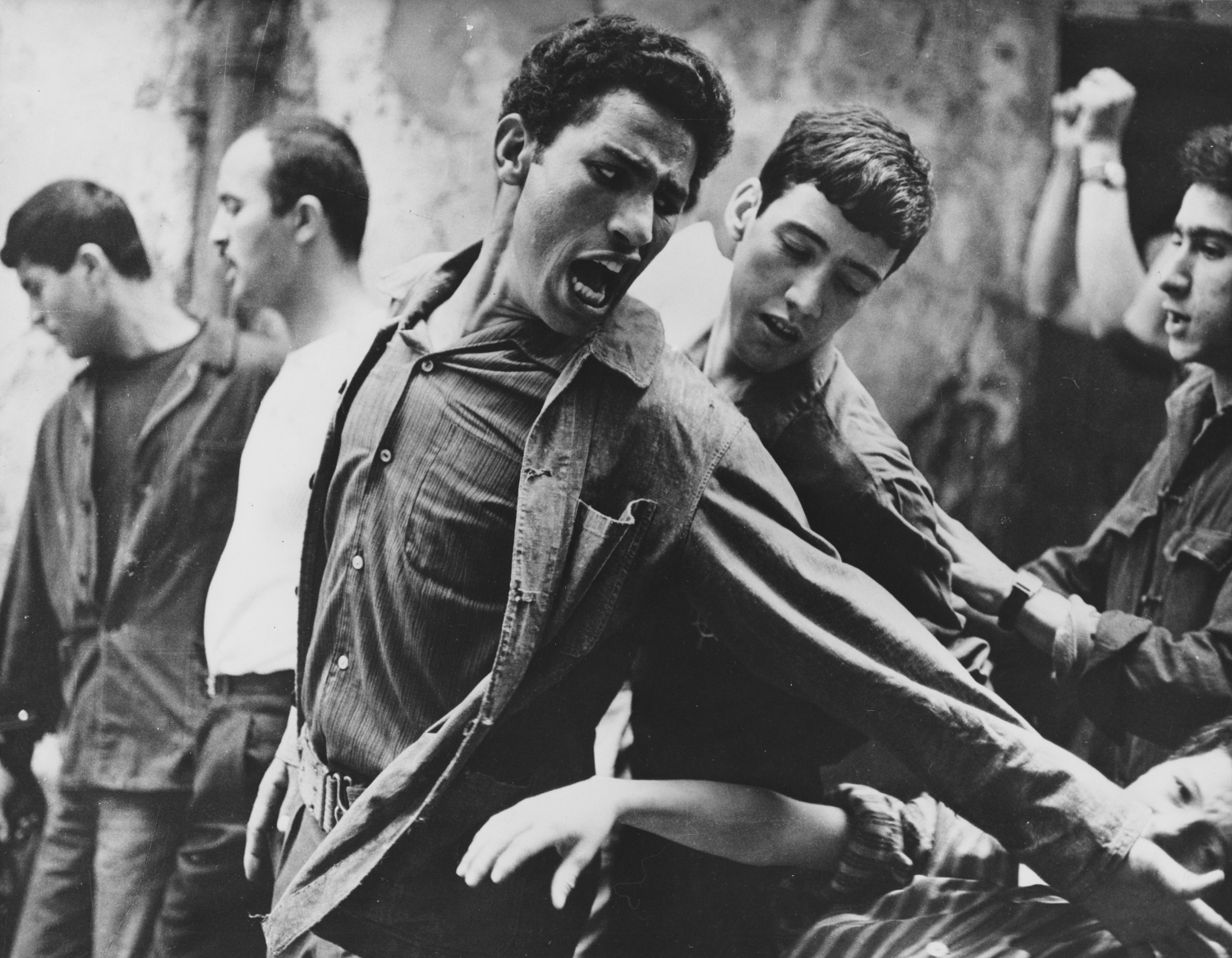

As production rose across the region, the pioneers of the New Arab Cinema busied themselves with bold and ambitious auteur-driven pictures. Some turned to neorealist and artistic studies of society, culture and identity, with films from Egypt like Youssef Chahine’s Cairo Station and Shadi Abdel Salam’s The Night of Counting the Years. The fights for independence would inspire many works, among them Algeria’s The Battle of Algiers by Gillo Pontecorvo and Chronicle of the Years of Fire by Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina. Winning the top prize at Venice and Cannes film festivals respectively, the two films boosted the profile and showcased the power of Arab cinema in the international arena.

The ever-shifting landscapes in the Arab world invited more filmmakers to come in and broaden screen stories. The Palestinian struggle and the shock of the 1967 Six-Day War inspired filmmakers such as Tewfik Saleh (The Dupes). Likewise, Ziad Doueiri (West Beirut) offered an unusual playful perspective on the Lebanese Civil War, while female directors such as Tunisia’s Moufida Tlatli (The Silences of the Palace) zeroed in on the position of women in the patriarchal society. On another front, exiles like the Palestinian Michel Khleifi (Wedding in Galilee) blazed a trail by filming on his homeland.

Thanks to the preservation and restoration efforts, these groundbreaking films are brought back into circulation. Carrying immense cultural and historical value waiting to be discovered, the Arab stories become not a legacy but a starting point to retrieve the memory – where to go from here?